If code is poetry, I think I’m illiterate. At least that’s how I feel every time I open a web page.

I’ve been programming for a couple of years, working my way through a bachelor’s degree in computer science majoring in machine learning. In the limited scope of my course, I’ve started to feel like I’m finally “getting” computers: that, hey I know my stuff. Realistically speaking, I’m delusional. I know a fraction of a fraction of a thin niche of computer science. I am miles from the programmers who have spent decades refining their craft, miles away from becoming the computer wizard that I want to be.

Nowhere is that more confronting than when I open a page on the web. They’re ubiquitous, and yet I don’t know how to make one. That’s frustrating. So, I decided to do something about it.

So. How do we Build a Website?

Okay. So, I buddy up with my friend James and we get to work planning out how to cobble together a website. I get to work on building up the front-end, and him the back-end. I’m already familiar with the basics of CSS and HTML, so my issue isn’t making “a website” per se: it’s making a website that isn’t just lazy text on a white background.

I start off by looking at other websites for ideas - doesn’t take long, it takes 5 minutes to discover 50 sites with bright and striking designs. Here’s the rub - I’m an envious kind of guy. I see they have parallax scrolling, they have 3D interactable graphics, they have awesome and complex text effects. I see this, and I want it all.

Thus begins the learning spiral.

I start out by discovering Three.js, a JavaScript library that uses WebGL to render 3D graphics in web browsers. At the time, I’m only passingly familiar with what WebGL is. I know it’s used to render things, but I don’t know how. Hence, I get to work reading about how graphics libraries work.

To put it simply, a graphics library is a collection of software that lets one program talk to the graphics hardware on your computer. For my purposes, that’s all I needed to know, and it’s the first line of Wikipedia. Unfortunately, I read a bit more and found it really, really cool - and promptly got lost in the world of graphics libraries, shaders, and the neat transformations that computers use to render a 3D object on a 2D plane. I won’t talk about it more now because I risk getting sidetracked (again) and I’ll definitely be writing a section about it on the miniprojects section of this website later. But, if you are interested, start with these:

After that tangent, I returned to familiarising myself with Three.js, finding very quickly that I didn’t need to know what rasterization and all those concepts were, because Three.js is pretty simple. You make a scene, a camera and a renderer. You add objects to the scene. You link the renderer with the scene and the camera while calling the render function. Then bam, you have a 3D graphic that can be embedded in a canvas in html. This led to the first working (locally hosted) prototype of our website:

You can also click here to see the page .

So, first prototype completed! Slight issue - we couldn’t figure out a way to add more content to it without things looking hideous. So, it was time to redesign.

Tinkering, Building, Rebuilding

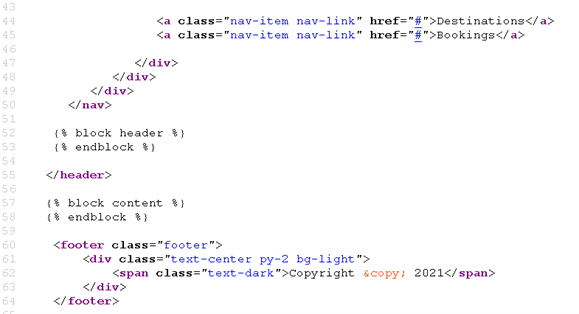

I had the idea of creating a sort of slide-card design after staring jealously at https://useplink.com/en/ for 15 minutes. I’d use <div> tags to create blocks which would move up and replace each other using CSS’s sticky positioning. The idea was to break the page into sections, sections that moved and replaced each other in a visually interesting way while retaining readability. To try keep things consistently visually engaging. I also added a Three.js graphic to each of the slide-cards. Here's the result:

Darn, writing that makes it sound so simple. Truth is, I learnt a lot about limitations in my understanding of CSS. I had a lot of misadventures in trying to get the formatting to pan out – spending a painful amount of time tweaking margins, padding, and display types. Half of my solutions work - but I’m not happy with them. I’m certain I can discover more concise ways of creating the visual effects that I made.

One of the things I found especially difficult was making the website resizable. Again, if you look at https://useplink.com/en/ and try resizing it, you’ll notice that the elements shrink fluidly. That wasn’t the case with Segfault Architects initially. If you made the website an itty-bit smaller, the text would fold in on itself, getting condensed by constant 20-pixel margins. The 3D graphics would stay the same size, leaving towering spinning-icosahedrons to dwarf the increasingly dense text. My solution was two-part: to write event-handling into my JavaScript to make Three.js objects resize properly, and to rewrite half the CSS up to that point so that the size of elements was based off the view-width of the screen. The CSS fix feels kind of clunky though and I’m sure I can find a more elegant alternative.

At the same time, I do feel a little bit proud. You see that back button up in the top left? This article’s really cool so don’t click it, try hovering over it instead. It’s a little thing; I know it’s not impressive, but I managed to make that button after I learned CSS pseudo-classes. It’s an <a> tag that changes its border and padding when you hover over it - one of the things I figured out how to make by myself as soon as I figured out you can tag selectors with hover. It bugs out if you hover over the top of the border, but still, it’s one of those little things that makes me smile.

What Could’ve Been Done Better & What’s Next?

There’re also more features I want to try implementing. I think it’d be cool if looked into adding page transitions, and I’m interested in making a mobile version of this website. In doing research to build this website, there’s a lot of things that I found I didn’t know about, like how JavaScript module aggregation helps improve website’s front-end performance - not just it’s tidiness. I’m reading up more on that after I finish writing this. I’m also planning to bug James incessantly until he walks me through exactly how the back-end of the system works. Look forward to that James.

As you start to learn a skill with any sort of depth, you’re very quickly confronted with how much more you must learn

before you can claim any sort of mastery. This has been the case, without exception, every single time I have tried to

learn a new concept in computing. It happened when I tried to learn about networking, when I started my units on AI in

university, and it’s happening now as I’m learning front-end website design. There is a lot I still don’t know. There’s

a lot I do know but am clumsy with. But I can now point to this, this whole thing, and say I know a bit.